History to opening.

- Home, index, site details

- Australia 1901-1988

- New South Wales

- Overview of NSW

- Telegraph lines

- Telegraph Offices

- Date stamps

- Forms

- Envelopes

- Rates

- Stamps

- Queensland

- Overview of Qld

- Telegraph lines

- Telegraph offices

- Date stamps

- Forms

- Envelopes

- Rates

- Stamps

- South Australia

- Overview of SA

- Telegraph lines

- Telegraph Offices

- Date stamps

- Forms

- Envelopes

- Rates

- Stamps

- Tasmania

- Overview of Tasmania

- General developments

- Reports

- Organisation

- Telegraph lines

- Telegraph Offices

- Date stamps

- Railway lines

- Forms

- Envelopes

- Rates

- Stamps

- Overview of Tasmania

- Victoria

- Overview of Vic.

- Telegraph lines

- Telegraph offices

- Date stamps

- Forms

- Envelopes

- Rates

- Stamps

- Ephemera

- Western Australia

- Overview of WA

- Telegraph lines

- Telegraph Offices

- Date stamps

- Forms

- Envelopes

- Rates

- Stamps

As the cable networks spread throughout the world, two issues emerged:

- how could the excessive charges levied by the cable companies be controlled?

- what protection did a country (or group of countries) have from the cable networks on which they had increasing dependence – either in war or in promoting commercial transactions.

In the context relevant to Australia, the concept of a cable from Canada across the Pacific had been discussed from the 1880s. In part such a cable was seen as being a competitor to the privately owned Eastern Extension and the mopoly it had established over cable traffic to Australia and New Zealand.

At about the same time, the United States - where private telegraph lines were flourishing - was also considering laying a cable from its west coast to the Far East (Japan and China).

From the early days of these considerations, the lead to lay a British Empire cable across the Pacific was taken on by the Canadian Sandford Fleming. Fleming had been charged with the responsibility, while he was the Chief Engineer for the Canadian Pacific Railway, to lay a land telegraph line from the Ottawa River to the Gulf of Georgia. He had a vision of developing a State owned and State operated cable system linking British Empire countries.

|

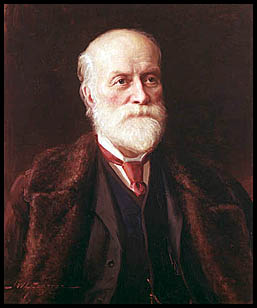

Sir Stanford Fleming (1827-1915). The great driving force to develop a Pacific Telegraph cable. Also was

|

Early references to a Pacific Cable are:

- the 1877 Inter-Colonial Conference in Sydney where the New Zealand representative was asked ti determine if the United States Government would be prepared to pay a subsidy towards the construction cost of a cable between New Zealand and the United States;

- an 1879 letter from Fleming to the Superintendent of the Canadian Telegraph and Signal Service suggesting that, as Canada would soon have complete overland telegraph system linking the Atlantic and Pacific oceans, it seemed reasonable that "the British possessions to the west of the Pacific Ocean should be connected by submarine cable with the Canadian line. Great Britain will thus be brought into direct communication with all the greater colonies and dependencies without passing through foreign countries" (Johnson, p.2).

As Johnson documents, developments over the next few years were a glowing testimony to bureaucratic obfuscation. If it had not been for Fleming's tireless efforts supported by several colleagues - including some of the Australians - the Cable would never have been constructed.

In very brief summary:

- A great deal of thought and some discussion took place over the following years with, at best, a quiet lack of support from the British Government. To prompt action, a company with the name Pacific Telegraph Company Ltd, London was established on 23 November 1876 - in anticipation of the Conference mentioned in the next point. The Secretary wrote to all relevant Premiers (click here for an example of this letter). John Pender wrote a reply soon after opposing the concept and offering to reduce the Eastern Extension tariffs which had long been criticised as being too high (the result of Eastern's monopoly).

- From 4 April 1887, a Conference of the Colonial Governors was held in London and Fleming, attending to represent the Canadian Railways, ensured the possibility of a Pacific cable was raised. The Secretary of State for the Colonies (Sir Henry Holland) noted in his opening address:

"(upon the question of telegraphic communication) the proposal to connect Australia with Canada by cable had been, from time to time, mentioned in connection with the Canadian Pacific Railway but the scheme is opposed by the companies which own the existing telegraph lines communicating with Australia. A very strong case would have to be made out to justify Her Majesty's Government in proposing to Parliament to provide a subsidy for maintaining a cable in competition with a telegraphic system which, at any rate, supplies the actual needs of the Imperial Government".

On another day during the Conference, the Canadian delegates had the opportunity to raise the telegraph cable issue. Fleming grabbed the moment to state his views about the proposed cable between Canada and Australia in a most eloquent and learned manner. The British Postmaster-General asked that the Conference not break-up without expressing support for Fleming's policy.

Towards the end of the Conference, Sir Alexander Campbell (Lieutenant-Governor of Ontario) siezed the momentum of opinion in favour of a Pacific Cable and suggested two resolutions - that the Canadian telegraph line opened the possibility of an alternative line of Imperial telegraphic communication through British possessions and that a thorough and exhaustive survey should be conducted without delay to determine the practicability of the concept.

- Two partial surveys had been conducted of aspects of the Pacific pertinent to cable laying:

the Cunard ship Challenger (1873-76) which had lowered a thermometer to the bottom off Halifax only to retrieve it shattered due to the significant pressure at depth. The results from her overall cruise were however recorded in 40 volumes.

the United States ship Tuscarora had made soundings between the Sandwich Isands and Australia

Neither survey could give an adequate description of what might be expected in laying a cable across the Pacific. But it was the British Government which had been tasked to organise the survey!! As Johnson writes - the inertia increased instead of diminishing.

Problems began as little as 12 days after the Conference ended. Fleming learnt that the Royal Navy had no intention of doing anything in 1897 and that a survey party would go to Australia in 1888 but for other purposes. In March 1888, the Governor of Victoria tried to move the activity along by suggesting "the cost (of the survey) to be defrayed by the treasuries of the United Kingdom, Canada and Australia".

Johnson goes on: "Here we have a good specimen of "how not to do it". First the attacking party: 'We want a survey". Then the defending party:'We have not a vessel to spare". Then the attacking party: 'We have a vessel". The defending party:'Well what about the cost?". The attacking party: 'We have a couple of public-spirited men who will put up one-half the cost'. Net result of first effort - silence on the part of the Admiralty.

Two years pass. The attacking party renews the attack supported by the representatives of all the self-governing colonies. The same weary round - 'No vessel. What about the cost of the survey? Have you got the cash on hand to make the cable?' The attacking party offers to pay two thirds of the cost. "Hold" says the party of inertia "I have just had an important thought. There must be an approximate estimate of the cost of the survey". "Hold" say their co-adjucators in the Imperial Government "we also have had a valuable thought - we can do nothing to show that the scheme is or is not impracticable until we know that funds are on hand for the construction of the cable". With such solemn fooling, another three years pass."

At least it was decided to send the Egeria to Australia to do some "special work". Unfortunately that ship was not head of for another two years.

- Another Inter-Colonial Conference among Governments was held in Ottawa 1894. There were no survey results to report despite the request for "an immediate survey" seven years previously. So the Ottawa Conference passed another resolution which was almost identical to that passed in 1887.

In addition, however, another resolution was passed. It was proposed by Mr. A. J. Thyme M.E.C. of Queensland and it read:

"Resolved that the Canadian Government be requested, after the rising of this Conference, to make all necessary inquiries and generally to take such steps as may be expedient in order to ascertain the cost of the proposed Pacific Cable and to promote the establishment of the undertaking in accordance with the views expressed in this Conference".

Within a month of the Conference rising, an advertisement seeking contractors to supply and lay a cable appeared in newspapers!!!!!!

- In September 1893, an unexpected difficulty was fortuitously identified. The French Government had, in February 1893, signed an agreement with the New Caledonia Cable Company through which the cable from Queensland to New Caledonia would be under the absolute control of the French Government. That link was, under some plans, to be the first of the cables leading to Canada - hence mitigating the objective of an "All Red" line.

An interesting additional initiative published in the Launceston Examiner on 18 August 1893 was that " the Government of Germany will contribute towards the expense of laying the Fijian and Samoan section of the Pacific cable via New Caledonia."

- The problem disappeared when Mr Bowell, from Canada, who was visiting Australia in October 1893, described four possible Pacific cable routes then being considered - none of which involved New Caledonia:

Route 1: Vancouver Island to Fanning Island and then to the nearest island in the Fiji group. From Fiji the cable would go either to New Zealand or to Norfolk Island where it would divide to the northern part of New Zealand and to a place near the boundary of Queensland and New South Wales (71,145 knots).

Route 2: Vancouver Island to Necker Island (a small unoccupied island about 240 miles from Hawaii) and thence to Fiji etc as per Route 1 (7,145 knots).

Route 3: Vancouver Island to Necker Island and then to Onoatoa or another island in the Gilbert group. Two branches would then be laid - one to New Zealand and the other to Queensland via San Christoval in the Solomon Group and on to Bowen. From there, the lines would run south to Brisbane and Sydney and west to Normanton in the Gulf of Carpentaria dn on to the Overland Telegraph line (8,264 knots).

Route 4: Vancouver Island to Necker Island and on to Apamana in the Gilbert group and San Christobel and Bowen. This route would exclude Fiji and New Zealand but would be the shortest route (6,244 knots).

As discussion was becoming more focussed, the Siemens Company submitted an offer to Canada about the middle of 1894 to lay a cable from Vancouver to Sydney within three years. The Company maintained that the existing survey was sufficient and offered to commence operations immediately, the line to cost two million sterling.

Surveys were also being conducted on a small scale. For example, in 1897, the Admiralty surveying ship Penguin was at Fiji when the mail left, after surveying the route of the proposed Pacific cable. The officers found the ocean bed between Fiji and Honolulu to be bad, being a strange mixture of submarine valleys and mountains, alternating with shallows.

A proposal was advanced in 1896 to discuss the proposal of laying an “All Red Pacific Cable” to consolidate both Imperial interests against private interests and Imperial interests against those of the USA. The Governments of Western Australia, South Australia and Tasmania were among those who did not support the proposal.

At the 1896 conference, the Secretary of the (UK) Post Office (John Lamb) noted:

"if you look at a map of the world, you will find that practically all the telegraphs of the world are centred on England; but under this arrangement (a U.S. cable to the Far East), a rival centre would be established on the west coast of America ... it is important to this country in every way that its position as the centre of telegraph communication should be maintained. Under present arrangements the British merchant should get his information first and he ought to get it cheaper than the American merchant”.

(quoted in Winseck, p.166).

At the 1896 Conference, a Pacific Cable Committee was formed to allot the shares of the venture amongst the six partners and to devise a scheme of joint control. In.1896, a committee was appointed to consider this matter but it was 1899 before it presented its report.Finally it was determined that the cable should be vested in a board of commissioners to be nominated by the Imperial Government and that the other Governments concerned should appoint administrators in proportion to their share of the undertaking. These shares were allotted in the following proportions: The Imperial Government and Canada, five-eighteenths each; and New South Wales, Victoria, Queensland and New Zealand, two-eighteenths each. The. colonies very properly brought pressure to bear on the Home Government, with the view of utilising British credit and a committee consisting of Lord Solbourne, Lord Aberdeen,the High Commissioner of Canada, the Agents-General of Australia and New Zealand, with others of the highest standing, met in November 1899, and the first arrangements were completed. Thus the long-deferred link became a live reality, just at the moment when Australian Federation became also an accomplished fact.

Western Mail (Perth)

12 May 1899.

The dream of an All English cable is still far from being realised. The Imperial spirit favours it but cash is not forthcoming in an equal degree. Canada is very willing. Our Eastern colonies are acquiescent - or a little more - but prudent as to the expenditure. The Imperial Government is in a saving mood and prefers battleships and cruisers to this gentler means of linking the colonies to each other and to Britain.

All that Lord Salisbury is able to offer for a line running from Vancouver via Fannng Island, Fiji and Norfolk Island to Queensland and New Zealand is a subsidy to the extent of 5/18 of the annual loss - the subsidy not to exceed £20,000. The subsidy would only last for twenty years and in return for it, the Imperial Government stipulates that Imperial messages shall have the right of priority and shall be charged only half-rates. There ís certainly nothing brilliantly generous about this offer. It is equally certain that unless the Imperial Government proves a little less cautious about bearing part of the burden, the cable will remain unlaid.

The cable is desired just as much in the interests of the empire as in those of trade and the chief arguments in its support are those relating to possible wars. When this is considered, Mr. Chamberlain's statement that the offer of his government is "liberal'" can scarcely be regarded as a remarkably accurate summing up of the state of affairs".

Launceston Examiner

10 September 1900.

"Notwithstanding the opposition which has been displayed in connection with this undertaking, it has been advanced another step by the opening of tenders for the work. The lowest is that of the Telegraphic Construction and Maintenance Company, for £1,886,000. The work is to be completed in 18 months. The route will be from Vancouver in British Columbia to Fanning or Palmyra Island from thence to Fiji or Norfolk Island and from thence to Queensland with a branch to New Zealand. The length of the cable will be about 8,000 miles and the longest stretch, from Vancouver to Fanning, a distance of 3,561 miles.

Great Britain and Canada will contribute five-ninths of the cost and the colonies of Victoria, New South Wales, Queensland, and New Zealand one ninth each: It is estimated that the annual cost will be between £150,000 and £160,000 a year and the revenue for the first 12 months £110,000, after which it is anticipated the deficit will gradually decrease and be wiped out in a few years. This will involve the colonies interested in a charge of £22,000 a year instead of the £30,000 they were previously paying the Eastern Extension Company. This amount will in a few years disappear by increasing revenue. Already we are reaping the benefit of the proposed competition by reduced rates and the safest plan to ensure a reasonable rate is to proceed with the Pacific venture

The present company contemplates an extension of the South African cable to Australia, and when the Pacific line is completed, there will be communication from north, east, and west.

One great drawback to the present service is the enormous extent of land lines which have to be maintained through sparsely populated country. Most of the settlement on the mainland is on the eastward while the cables come in on the north. One land line runs right through the continent, while the other skirts its western shore. The Pacific line will come into communication with the east part of the continent and there will be less chance of delays. With the two additional cables, the probability of being entirely cut off will be reduced to a minimum and it will be a good day for Australia when the first message comes through on the "all red" line".

In 1901 the "Pacific Cable Board" was formed with eight members: three from Britain, two from Canada, two from Australia and one from New Zealand. Funding for the project was shared between the British, Canadian, New Zealand, New South Wales, Victorian and Queensland governments.

In mid-1900, The Pacific Cable Board's Report was finalised and the process of tendering for the construction of the cable commenced.

Argus

28 February 1901.

The contract for the Pacific (all British) cable (says our London correspondent) bears the signatures of the Chancellor of the Exchequer (Sir Michael Hicks-Beach), Mr W. H. Fisher, one of the Lords Commissioners of the Treasury, Lord Strathcona and Mount Royal, Mr. Henry Copeland, Sir Andrew Clarke, M. W. P. Reeves and Sir Horrace Tozer.

The total amount of the contract entered into with the Telegraph Construction and Maintenance Company is £1,795,000. This amount is made up of:

- the Vancouver-Fanning Island section, which has to be completed by December 31 1902, is £1,067,102.

- the Fanning Island to Fiji section, which has to be completed by the same date, is £388,358.>

- the three remaining sections - Fiji to Norfolk Island, Norfolk Island to Moreton Bay and Norfolk Island to New Zealand, which all have to be finished by June 30, 1902, is £339,040.

Goulburn Herald, 11 April 1900:

"The Imperial Pacific Cable Board, having carefully considered the proposed agreement between the colonial governments and the Eastern Extension Telegraph Company, has unanimously concluded that the company's offer would very materially injure the revenue to be derived from the Imperial Pacific cable. Fearing that the Pacific cable project might be delayed if the Eastern Extension Telegraph Company's offer is accepted, the board recommends the Australian governments to endeavour to conclude another agreement on the lines of the existing contract with the company, to expire when the Imperial Pacific cable has been laid".

THE PACIFIC CABLE.

LONDON, February 28.— The Pacific Cable Board has disapproved the agreement entered into by New South Wales with the Eastern Extension Australasia and China Telegraph Company.

Brisbane Courier and many other Queensland papers

11 March 1902.

" One of the fruits of the labours of what has been called the Continuous Ministry, which Queenslsad is now about to receive, is the construction of the Pacific Cable, the laying of which is being commenced at Southport today. No State in Australia has fought so consistently or effectively against the Eastern cable monopoly as Queensland has and today her efforts are being crowned with success. And yet it seems strange that hitherto the candidates at the general election seem to have ignored the subject in their speeches in attacking or defending the administration of affairs by the Government".

Brisbane Courier: 29 April 1902

PACIFIC CABLE.

Great success appeared to have followed the laying of the first sections of the Pacific cable, particularly on the New Zealand end, where a great deal of business has been done (NOTE: The Southport-Doubtless Bay cable was only completed on 26 March). The immediate effect of the increase, which comes through Queensland, has been to put great pressure on the lines between Queensland and the Southern States, which are under difficulty in coping with the amount of work thus provided.

In May 1902, the PCB gave a provisional date of opening as 15 November.

On 24 November 1902, a number of newspapers carried the announcement:

"PACIFIC CABLE LONDON, Saturday.

The Pacific Cable Board will commence operations on December 8".

The Brisbane Courier, on 8 December 1902 carried the following:

"The Pacific Cable, which was completed about a month ago, will be opened to traffic this morning. It is not expected that there will be any ceremony in connection with the event - that having been celebrated already. The work of transmitting the messages from Southport to Brisbane will be undertaken by the cable staff, which will be somewhat strengthened for the purpose. It is not expected that there will be any undue pressure on the Intercolonial line by the increased work but arrangements have been made, should such an event occur, to temporarily deviate some of the business over other lines to the South".

Launceston Examiner

5 November 1902

The Pacific cable, which has just been completed, furnished another link connecting the Australasian states with the outside world. It will enable their people to breathe more freely, for it makes for security in time of war and, being an all-British line of communication, it is more under our own control. Its location also removes it from the political storm centres of Europe and, although it may be interrupted, there is less likelihood of an event of this sort than in the old world lines. Moreover, it is not in the hands of a private company but is a national undertaking in which Australasia holds a share. Already the Commonwealth has reaped substantial advantages from the project. It caused the Eastern Extension Company to reduce its rates and also to couple up South Africa with these states.

Unfortunately, in the eagerness to reap the monetary advantages, concessions have been granted that are likely to seriously operate against the financial success of the new venture. It was opposed strongly by some of the important mainland journals but now it is an accomplished fact and the Commonwealth will have to bear its share of any loss. It is to be hoped we shall hear no more disparaging comments. Cables are an important adjuncts of commence. Whether trade follows the flag is a debatable point but it certainly follows those routes which are best supplied with means of communication. Whether any large amount of trade will eventually be opened up with Canada, time alone can demonstrate but the Pacific route to the old country is increasing in favour and, before long, we may expect to see a steady stream of travellers in that direction. The Dominion people deserve encouragement for their enterprise in bridging the continent. British Columbia bids fair to become an important portion of the Empire. and Vancouver stands as its western gateway. and promises to become an entrepot of trade with the Far East. It has been prophesied that the Pacific will in the future become the arena of national activity and, if so, then the nation which has rapid means of communication in its hands is the best equipped for future contingencies. The cable will strengthen the Empire, and will add to the security of its southern possessions.

In July 1907 Sir Henry Primrose was appointed chairman of the Pacific CableBoard.

In February 1918, Sir William Mercer was appointed chairman of the Pacific Cable Board.